Introduction

My journey to becoming a teacher librarian (TL) began in 2012 as a means of adding another string to my professional bow. Despite having never worked as a teacher librarian, I reasoned that this qualification would enable me to continue teaching, but in a more flexible environment than that of a primary classroom teacher. Also, I have always had a keen interest in children’s literature and inquiry-based learning so it seemed a good fit for my post-graduate specialisation. Looking back, I must admit I did not fully understand the scope and scale of the profession, but now as I approach graduation I know I have made the right choice, personally and professionally.

Early in my studies I realised I had little knowledge and understanding of the actual role of a modern school library and the teacher librarian. In ETL401 and ETL504 we explored the changes in the role of the 21st century TL and the developments in school libraries and I can now reflect on my developing confidence in identifying and defining these roles.

The role of the school library

In my career I have taught in over ten primary schools and it is sad to say that I have only worked in three schools with ‘fully functioning’ school libraries. Many have rooms filled with books so it is no surprise to me that people think, “all librarians do is just check out books, right?” (Purcell, 2010). Reflecting on my studies and professional practice it has become clear how and why a school library should operate.

The key role of the school library is to support the classroom teachers and their curriculum needs (Collins and Doll, 2012). A school library does this by carefully selecting resources, and by encouraging and enabling the students and teachers to access and use these resources. This sounds simple enough, but in reality getting a school library functioning at this level is difficult. As seen by the changes in the Australian Curriculum, the students’ and teachers’ needs are constantly changing. The school library needs to be a dynamic resource centre that is ready and able to adapt to such changes in curriculum, as well as changes in technology.

In this information rich digital world more and more students rely solely on electronic resources for their research and possibly for their recreational reading as well (Corbett, 2011). With this change in resource medium in mind there also needs to be a change in mind-set for school libraries regarding how the resources are accessed and used, and how the library space is utilised. When I reflect on all a school library can offer; from Makerspaces, to online 24 hour access, and spaces for the entire school community to use, I find the future of school libraries to be an exciting one.

The role of the teacher librarian

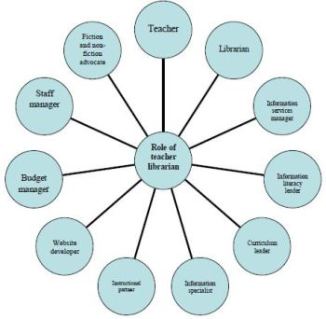

The role of a teacher librarian is multi-faceted. ASLA (2014) describes the teacher librarian as a uniquely qualified person because they bring curriculum knowledge and pedagogy together with library and information management knowledge and skills. Purcell (2010) looks at more specific roles and suggests teacher librarians are leaders, instructional partners, information specialists, teachers and program administrators. Herring (2007) elaborates even further and proposes a teacher librarian having eleven roles to consider. See below.

Image. 1. Herring (2007) Role of a teacher librarian

Image. 1. Herring (2007) Role of a teacher librarian

While I was reflecting on the role of a teacher librarian I was reminded of a promotional video entitled ‘Teacher Librarians at the Heart of Student Learning’ from the Washington Library Media Association (2013).

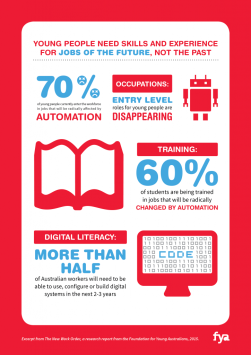

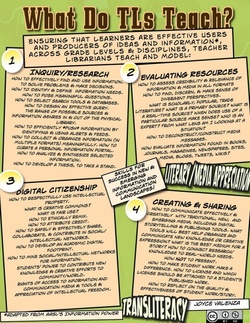

In this video you meet a number of school librarians describing and advocating their role. They break it down to three specific areas: Information Technology Instruction, Reading Advocacy, and Information Management and Service. I agree with these as components of the role but what struck me most from the video was a statement about the ever increasing responsibility of the teacher librarian to ensure students have skills in digital literacy as well as general information literacy.

Sarah Applegate, a teacher librarian from River Ridge High School in Washington explains that, “Getting the stuff (information) is not the problem. It’s about what is the student going to do with it and what kind of new knowledge are they going to produce out of it. And that’s where the thinking comes in – and that’s a massive change for library work and something that makes it exciting.” This quote made me reflect on an info-graphic I saw recently, which brings home the importance of including digital literacy in our curriculum. And who is better placed to do that than a teacher librarian.

By reflecting on the role and names you might give the areas within the role, I have come to believe that, ultimately, the teacher librarian’s role is the same as that of the school library: to best meet the needs of the users (students and teachers) to improve student outcomes. By carefully selecting resources to meet the needs of the students and teachers, a successful teacher librarian will also collaborate with teachers to plan and implement digital literacy, information literacy and literature programs that result in positive student learning outcomes (ASLA, p.3, 2004).

From these understandings I have developed my own personal philosophy as a teacher librarian.

Personal Philosophy

As a 21st century teacher librarian I am passionate and committed to:

- Ensuring the library is the heart of the school, where reading, research, and collaborative teaching and learning co-exist.

- Being a dynamic partner and leader in my school and strive to align the library’s vision with the mission of the school.

- Fostering teaching and learning to develop each student’s creative and critical thinking skills enabling them to become successful, life-long learners.

- Integrating ICT and Web 2.0 technologies into the curriculum, to encourage students become information literate, critical thinkers and users of information in all forms.

- Promoting a culture of reading across the school to help create a community of passionate, independent readers.

- Developing a collection that meets the teaching and learning needs of the teachers and students, with access to a wide range of print, digital and online resources.

Collaboration is Key

With these roles clearly established in my mind I move onto an area that has had a huge impact on my learning – collaboration. I believe collaboration is the cornerstone for a successful school library program. I have come to understand how vital it is for the teacher librarian to foster and maintain a good relationship with their school principal. Rosenfield & Loertscher (2007) advocate three key ways to gain the support of your principal: build professional credibility, communicate effectively and work to advance school goals. School leaders can only be open to the potential of the school library and the immense value it provides if you demonstrate this to them. Teacher librarians must show initiative, and seek out this collaboration by actively advocating the virtues and values of their library. Once you have your principal on board, collaborating with the teachers to get the best possible outcomes for the students is the next step. With successful collaboration you should find their enthusiasm being passed down to the students (Lamb, 2011).

A good example of how a teacher librarian can encourage collaborative relationships was when creating a pathfinder in ETL501. The interactive nature of such Web 2.0 technologies encourages stronger connections between teacher librarians, their students, and fellow teachers (Glassman & Sorenson, 2010). Pathfinders are a dynamic way to provide information because they have been developed for a specific group of students and a specific subject area. When working with primary school children pathfinders launch students straight into the research process by eliminating some of the initial anxiety and stress about where to start (Kuhlthau, 1991 cited in Hemmig, 2005). And in today’s information rich environment, pathfinders empower students to work more efficiently and effectively and in turn strengthens relationships with the teacher librarian and the services they offer.

Challenges facing teacher librarians

As I reflect on my four years of study I also acknowledge the many challenges facing TLs. In my experience as a primary school TL time restraints are one of the main obstacles. Most primary schools with a qualified TLs will see each class for a library lesson each week. Depending on this size of the student population, this usually means the TL has a heavy teaching load and very little time to fulfil the other duties mentioned in the section above (The role of the teacher librarian).

If the key to being effective is collaboration, then time needs to be given for TLs to meet with class teachers to plan the program to best meet their needs. Unfortunately, the library lessons are often timetabled during class teacher release/planning time, which further complicates trying to collaborate. In addition to collaborating to best meet learning outcomes for students there is the need to collaborate with teachers to best develop the library collection.

As we learned in ETL503 resourcing the curriculum is an enormously important component of an effective school library. This subject was very beneficial as it took us from the very beginning of planning the collection to meet the standards, procedures and practices set by the Australian Curriculum and teaching and learning programs (DETA, 2013). Finding the time to maintain the library collection, on top of the heavy teaching load, can be a real challenge for primary school TLs.

Despite the time restraints, it is imperative that the school library collection is maintained and consistently evaluated, to identify any strengths and weaknesses. This allows the TL to build the collection to best meet the needs of its users, (Bishop, 2007) so the collection remains relevant (Kennedy, 2006). In this age of digital information overload, a collection can lose its relevance to its users very quickly. By reading Hart (2003) I learned that collection evaluation should be conducted regularly and systematically to maintain its relevance.

This is especially important when considering a school’s electronic and digital resource collections and the management and integration of these into their existing collection. There are so many issues to consider with digital resources that I had not considered before, such as access and ownership (subscriptions and renewals etc.), licensing, software and applications, the longevity of the resources and the equity of these resources. In light of budget restraints, these types of resources also need to be evaluated in economic terms. I recently conducted an audit of my school’s Britannica Image Quest subscription. This data base costs us approximately $3000 a year and yet we only have had 319 queries. That worked out to be $9.40 per image! As such we have decided not to renew this subscription and find a more cost effective solution for 2016. An alternative to direct our students to is https://www.flickr.com/creativecommons/ and the added bonus is that it also opens up an opportunity for a discussion around copyright and creative commons licences.

Challenges I have faced

Early on in the course when I was introduced to the twelve ‘Standards of Professional Excellence for Teacher Librarians’ (ASLA/ALIA, 2004) I felt overwhelmed. I could not imagine how any one person could possibly meet all the criteria. As my studies progressed I realised these standards are simply an intertwining set of guidelines that we must strive to achieve over time. My studies during ETL504, Teacher Librarian as Leader, helped to guide me with this understanding. I was daunted by the prospect of trying to be a leader in my school, especially as a newly trained TL.

Through the readings of Donham (2005) and Collins (2001) I gained encouraging advice about becoming confident in the role and developing leadership qualities. Collins suggests we try to understand what we are/can be best at and what we aren’t/cannot be best at. He believes great leaders don’t strive to be there best at everything but challenge themselves to be outstanding at some components of a role and make sure the other components are acceptable. Similarly, ETL504 taught me to pursue what you are passionate about because to sustain enough energy to be a good leader, you need to ensure at last one component of the role generates real enthusiasm and passion.

Another challenge I faced was in ETL505 Describing and Analysing Resources. As I am new to the library profession I found this component of the course to be the most challenging. On reflection I can now understand why the need arose to develop the Resource Description and Access (RDA) standards. I have also benefited from learning about other methods of achieving consistency such as the standardisation of vocabulary, the use of subject headings and the detailed assignation of classification numbers.

While I agree that Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) is a phenomenal classification scheme, I feel from the position I am in as a primary school TL, assigning of RDA access points and word based subject access is ultimately more effective than DDC numbers. While student in schools such as mine do have an understanding of how the DDC system is organised, they are still more likely to search for a resource using a subject heading or an author’s name.

A-ha moments!

There have been several moments of discovery during this course that stand out for me. The first and most powerful has been gaining even further understanding of the power of reading and storytelling. During ETL402 I examined the concept of literary learning and how it can be used to enhance student learning outcomes. This subject further developed my knowledge of the diversity of children’s literature and reaffirmed that school library programs can be central to lifelong learning.

The readings of Haven (2007) demonstrated that students with good knowledge of story structure comprehend better and their informational memory and recall is also improved. Haven (2007, p.104) wrote that, “as humans we all think, live and learn through stories.” These readings lead me to further research and helped me to consider the importance of traditional storytelling in achieving outcomes such as in the Cross Curriculum Priority: Sustainability. Haven’s findings demonstrated that by using literature students enter a relevant context where they develop empathy and connect to nature in a positive way. The same can be said for literary learning across the entire curriculum. For example: Abstract scientific concepts that can often be met with resistance by young students can be more approachable when the reader is connected to the characters and the dilemmas they face (Almerico, 2013).

Another moment of insight was in creating the digital pathfinder. This process was enormously beneficial for me in developing my Web 2.0 skills, but also in creating a helpful resource for teachers and students. Rather than simply pulling out print resources from the library, or printing off information downloaded from the internet, the pathfinder simply provided a ‘shortlist’ of suggested resources they could use. The students then still have to evaluate the resources and question which resource is best for them and why. In time they will begin to see the relationships between sources and learn to question how to best use a resource to meet their needs (Hemmig, 2005).

Pathfinders are also helpful in alleviating some of the daunting feelings we feel in those first stages of research because it gives the students a starting point, but still requires them to think critically about which of the resources they will actually use. This leads to my final a-ha moment, which was when I discovered Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process (ISP) and her Guided Inquiry (GI) concepts. Understanding these processes and concepts early on in my learning journey was extremely valuable and they have stayed with me throughout the course. This is a wonderful model, developed over several decades of studying student’s thoughts, actions and feelings and I have referred to it often in my own studies and also strive to apply it during my work.

Conclusion

My learning experiences throughout this course have created a solid foundation on which to build my future teacher librarian career. With the ‘Standards of Professional Excellence for Teacher Librarians’ (ASLA/ALIA, 2004) to guide my development I can identify my areas of strength and weakness. I will strive to be the teacher librarian as described in my Personal Philosophy and hope the students I teach benefit greatly from the library program I implement.

Bibliography

Almerico, G. M. (2013). Linking children’s literature with social studies in the elementary curriculum. Journal of Instructional Pedagogies, 11.

Australian School Library Association (ASLA) and Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA). (2004). Standards of professional excellence for teacher librarians.

Bishop, K. (2007). Evaluation of the collection. The collection program in schools: Concepts, practices and information sources (4th ed.) (pp. 141-159). Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited.

Collins, J. (2001). Good to great: why some companies leap and others don’t. New York, Harper Collins.

Collins, K. & Doll, C. (2012) Resource provisions of a high school library collection. School library research: Research journal of the American Association of School Librarians, 15. Retrieved from: www.ala.org/aasl/slr

Corbet, T. (2011). The changing role of the school library’s space. School Library Monthly. 27(&), 5-7.

Department of Education, Training and Employment (DETA). (2013). Curriculum into the classroom (C2C). Retrieved from: http://education.qld.gov.au/c2c/

Donham, J. (2005). Enhancing teaching and learning: a leadership guide for school library media specialists, 2nd ed. Neal Schuman, NY.

Glassman, N. & Sorenson, K. (2010). From pathfinders to subject guides: One library’s experience with LibGuides, Journal of Electronic Resources in Medical Libraries. 7(4).

Haven, K. F. (2007). Story proof: the science behind the startling power of story. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Hemmig, W. Online pathfinders: Toward an experience-centred model. Reference Services Review, 33(1), p.66-87

Herring, J. (2007). Teacher librarians and the school library. In S. Ferguson (Ed.) Libraries in the twenty-first century: charting new directions in information. 27-42.

Kennedy, J. (2006). Collection Management: A concise introduction. Centre for Information Studies, Wagga Wagga, Australia.

Kuhlthau, C. (2010). Building Guided Inquiry Teams for 21st-Century Learners. School Library Monthly. 26(5). 18.

Lamb, A. (2011). Bursting with potential: Mixing a media specialist’s palette. Techtrends: Linking research & practice to improve learning, 55(4), 27-36.

Purcell, M. (2010). All librarians do is check out books right? A look at the roles of the school library media specialist. Library Media Connection. 29(3), 30-33.

Rosenfield, R. & Loertscher, D. (ed.) (2007). Towards a 21st-century school library media program. Scarecrow Press Inc. Lanham, Maryland.

Schrock, K. (2009) The 5 W’s of web site evaluation. Retrieved from: http://www.schrockguide.net/uploads/3/9/2/2/392267/5ws.pdf

Seuss, Dr. (1978). I can read with my eyes shut. Random House: USA

SCIS Connections School Library Collections Survey. (2013). Retrieved from:

Walter, V. & Weisberg, H. (2011) Being indispensable: A school librarian’s guide to becoming an invaluable leader. ALA Editions: Chicago

Valenza, J. (2011) Manifesto for 21st Century Teacher Librarians. Retrieved from:

http://www.teacherlibrarian.com/2011/05/01/manifesto-for-21st-century-teacher-librarians/